Quick Fix

By John Maday

Reprinted with permission from Drovers/CattleNetwork

November 15, 2011

Can producers improve the value of their calves in a single generation by upgrading their bull selection? An ongoing study at Gardiner Angus Ranch, Ashland, Kan., suggests that in some cases, yes they can.

The Southern Carcass Improvement Project is a collaboration between Gardiner Angus Ranch, Kansas State University and Virginia Tech to determine how much carcass improvement can be made in one generation, using high-carcass-value Angus AI bulls on typical Southern-origin beef cows, representing typical Bos indicus-influenced genetics most often found in Southern states.

Southern calves typically sell at significant discounts to those in Northern markets. Not all those calves deserve their reputation, but the trend is clear. For the week ending Oct. 15, 2011, for example, 500- to 550-pound calves in Texas sales averaged $141.22 per hundredweight, while calves in the same weight class in Nebraska averaged $156.92 — a difference of more than $15 per hundredweight or $78 per head.

Transportation costs can account for some of the Southern discount, but the main factor is buyer perception that the calves, typically mixed-breed, multi-colored types with significant Bos indicus influence, will underperform at the feedyard and packing plant. With that in mind, the researchers designed the study to measure how an infusion of top Angus genetics could affect calf value in a single generation.

Mark Gardiner, of Gardiner Angus Ranch, says bull customers often ask just how much change they could expect in one generation if they used high-quality Angus AI bulls. "We're very data-driven," he says, explaining that he wanted real-world evidence before answering the question.

Gardiner acknowledges that many Southern producers value some level of Bos indicus genetics in their cow herds for heat tolerance. Depending on their priorities, some might use Angus bulls in a terminal-cross system, raising replacement heifers from a different pool of cows. But he says many of his customers in the South raise crossbred Angus-sired replacement heifers. Many, he says, use crossbreeding programs targeting one-quarter Bos indicus, and some have shifted their cow herds to almost 100 percent English genetics.

Direct Comparisons

The Gardiners initiated the SCIP project in 2008, planning a study design utilizing embryo transfer and artificial insemination that would allow direct comparisons of multiple calves from Southern-breed dams, sired by different bulls.

The group purchased 22 typical Southern cows from Georgia, Mississippi and Texas to serve as donors, and flushed the first set of embryos in July 2009. For the control group, the researchers used semen from nine representative "Southern" AI bulls, all from Bos indicus-influenced breeds. For the treatment group, they selected three proven Angus AI sires for the traits of merit, including growth, muscling ability and marbling potential. They randomly selected bulls from the two sire groups for each mating.

The first set of calves was born during April and May of 2010. They spent the summer grazing at Gardiner Angus Ranch, were weaned in November and backgrounded on wheat pasture until March 2011 when they shipped to Triangle H Feedyard, Garden City, Kan. The 57 calves went to slaughter in two groups at the end of June and July. The slaughter group included 35 Angus-sired calves and 22 Southern-sired calves. Of the donor cows in the study, six had progeny from both Angus and Southern bulls, allowing direct comparisons of the sires' contribution to calf performance and value.

Throughout the entire study, both groups of calves were managed the same. All the calves received three implants — one as calves, one as yearlings and one in the feedyard.

The researchers have collected data at several production stages to compare the value of each group of calves. Sixty days after weaning, for example, they surveyed a group of 95 experienced feedyard managers, stocker producers and auction market operators from a dozen states, asking them to gauge the value of each of the two SCIP sire groups using pictures and a brief written description of the sires and dams represented by each group. This allowed a market value assessment at the post-weaning stage of production without actually selling any of the project cattle. They asked each participant to value the two sire groups, according to what they would be willing to pay given market conditions at the time the survey was completed.

All of the survey participants valued the Angus-sired group higher than the Southern-sired calves, with the average price differential exceeding $9 per hundredweight at 700 pounds. This difference amounted to 7.8 percent and was statistically significant.

The researchers also collected DNA samples from all the cows, sires and calves in the study, using the Igenity profile including ratings for marbling and percent USDA Choice. Early results show significant improvements in just one generation. One Georgia donor cow in the study, for example, has a "4" DNA-rating for marbling and percent Choice on the 1-to-10 Igenity scale. Using embryo transfer and AI, the researchers mated her with the Gardiner Angus sire "Predestined" and produced five Angus-sired calves. Each of the calves had an Igenity marbling score of 7 or 8, and all five head graded Choice.

Early data showed an advantage in calf and yearling traits for the Angus-sired calves. Angus-sired calves in the study had gestation lengths averaging 8.3 days shorter than Southern-sired calves. Their birthweights averaged 8 pounds lighter. Weaning weights were 6 pounds heavier, and yearling weights for Angus-sired calves averaged 52 pounds heavier than those for Southern-sired calves in the study. All the figures except weaning weight were statistically significant.

Carcass Differences

In late September, Gardiner Angus released carcass results from the progeny groups that went to slaughter over the summer. All the Angus-sired and Southern-sired calves went to slaughter at the same age, rather than at weight or backfat endpoints. So some of the lighter, lower-value animals could have finished at heavier weights and perhaps better quality grades with longer time on feed, but they also would have incurred higher feed costs.

The results show considerable differences. Two-thirds of the Angus-sired calves graded Choice, while none of the Southern-sired calves graded higher than Select. On average, the Angus-sired group finished with marbling scores that were 103 points higher, ribeye areas that were 0.96 square inches larger, 0.12 inches more backfat and 61 pounds heavier carcass weights compared with the Southern-sired group. While USDA yield grades were similar for both groups, the differences added up to an average carcass-value advantage of $134 per head for the Angus-sired group. The Angus-sired calves had higher feed intake in the feedyard, resulting in $41.31 higher average feeding costs, so the net economic advantage averaged $92.72 per head.

Gardiner says producers' responses to the results have ranged from surprise at the magnitude of change to "I could have told you that," from producers who have used similar bulls in their Southern cow herds.

Gardiner points out that the Angus bulls used in the test are not just average bulls but rank in the top 1 to 5 percent of the breed for multiple traits, including carcass merit. If producers want to achieve these rapid, one-generation improvements, he recommends they use top AI bulls or sons of top, proven bulls with high ratings for growth and carcass traits.

The Gardiners weaned the second group of 57 calves coming through the study this fall, weighed them and collected DNA samples. They'll spend the winter on forage — wheat pasture where available — with protein supplements and move to the feedyard in March.

Last year, Gardiner says, the AI matings produced a slightly unbalanced calf crop, with more Angus-sired calves than Southern-sired, so this year the group purposely aimed for more Southern-sired calves, resulting in 35 of those in the study compared with 25 Angus-sired calves. The full two-year study will generate data on more than 100 calves from the same group of donor cows, with direct comparisons of Angus-sired versus Southern-sired calves from the same dams in many cases.

Gene Therapy

A series of case studies helps illustrate the effects of a few of the matings.

The researchers collected DNA samples from each animal in the study, using the Igenity profile to rate them for marbling score and Choice percentage. One of the donor cows, from Georgia and of mixed breed, rated "4," a low score for marbling and Choice percentage. Using embryo transfer, she was mated to a top Angus sire, GAR Predestined, with an Igenity score of "8" for the same traits, and produced five progeny. All five graded Choice and tested at either "7" or "8" for marbling and Choice percentage in the Igenity profile.

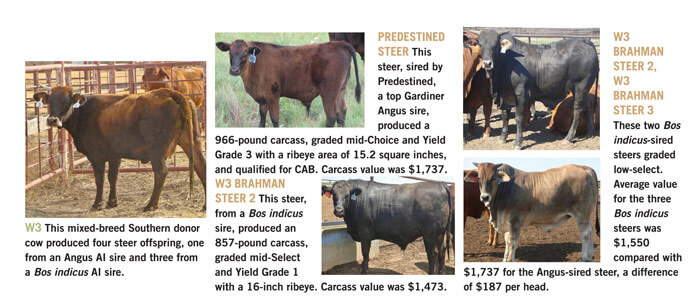

One mixed-breed Texas donor cow produced four progeny in the study — three from a Bos indicus sire and one from a top Angus sire. At slaughter, the Angus-sired calf weighed 966 pounds, graded mid-Choice and Yield Grade 3, qualified for Certified Angus Beef and had a total value of $1,737. The Southern-sired calves graded low- to mid-Select, with an average carcass value of $1,550, a difference of $187 per head.

In another example, a donor cow produced one Angus-sired heifer calf and three Southern-sired steer calves. The Angus-sired heifer graded Choice, while the Southern-sired steers all graded Select, and the heifer topped two of the three steers in carcass weight and ribeye area. At slaughter, the black heifer had a value of $1,657 compared with an average of $1,577 for the Southern-sired steers, a difference of $80 per head.